Afghanistan: Helping children who simply do not know who they are

Zuhra,* a 20-year-old Animator, worked at a child-friendly space in a reception and transit centre for Afghan refugees returning home. As an Animator, she led recreational and social activities for children in these spaces but also ensured they participated in them.

However, Zuhra is now one of the many women aid workers no longer allowed to work with national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or the United Nations, following the Taliban’s ruling.

She explains: “I love working with separated and unaccompanied children. I feel happy when I see them happy and playing. I miss them, since we [women] are no longer allowed to go to work. I am sad, and I hope the negotiations for us to return to work will be successful very soon.”

Afghan refugees are the world’s third-largest displaced population after Syrian and Ukrainian refugees. Currently, at least 8.2 million Afghans are hosted across 103 countries, the majority living in Pakistan and Iran. However, many Afghan refugees and undocumented returns are heading back home due to a lull in conflict after the Taliban takeover in August 2021, rising living costs in Iran and Pakistan, and the desire to rebuild their lives after decades abroad.

Children at transit centres

Zuhra told us about her work and the current situation in Afghanistan.

“As Afghans arrive back home, they are received at integrated reception and transit centres established by aid agencies in the border provinces of Herat, Kandahar, Nangarhar and Nimroz.

“We receive approximately 30 to 50 children from Iran or Pakistan every week. At these transit centres, Afghan people returning home are welcomed, registered, and given voluntary return and settling assistance, including cash assistance, shelter materials and non-food items. Some return with their children and sometimes with separated children who either lost their parents or lack identity documents, such as passports, and simply do not know who they are.

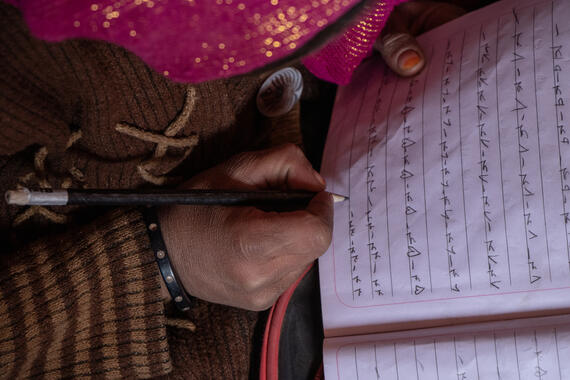

“My job is to help children, mainly separated and unaccompanied minors. I assist with ensuring and maintaining an environment that promotes physical, social and emotional safety and development for these children through arts, crafts, games and other child-friendly activities. Children get to relax and open up about their situation through these activities, including painting, drawing, storytelling and play.

“I am the only child-friendly space Animator at the transit centre. This makes me the only entry point into understanding the situation and needs of separated and unaccompanied children who arrive. Most have endured sad and traumatizing situations, but I feel satisfied that I play my part in helping them, and that the activities we offer provide them with some needed respite and a way of learning to understand and manage their emotions.

“From there I can tell which child needs additional attention and what type of support they require. I refer them for specialized help if needed.

“Without this service, some unaccompanied and separated children may become vulnerable to all sorts of risks, such as child labour, sexual exploitation and physical abuse. Once we refer them to aid agencies and other institutions their needs can be addressed with individual, tailored support, and they will also be protected. This is why this particular type of support is very important.”

This importance was highlighted in recent policy debates focusing on the situation of unaccompanied and separated children from Afghanistan. According to UNICEF, Afghan girls are exposed to protection risks including early marriage, domestic and intimate-partner violence, honour killings and sexual violence. Afghan boys also suffer protection risks, including sexual exploitation and forced recruitment into armed conflict.

Girls and boys are exposed to hazardous labour practices, contact with landmines and violence at home. In addition, Save the Children estimates that 1 million children are currently engaged in child labour in Afghanistan, as family incomes have plummeted.

My job, my lifeline

Zuhra continues: “After the Taliban’s 24 December ban on Afghan women working for national and international NGOs, we were among the few allowed to continue working because the authorities thought we were providing essential services. But later, we were told to stop.

“I understand negotiations are under way, and I can only hope that we can return to work for the sake of the children and people returning to Afghanistan.

“In addition, this job is the only hope for my dreams and my family’s welfare. At only 20 years old, I am already the breadwinner. Without income, my family will starve. Employment is hard to find these days, so I am hoping we can be allowed to return to work.”

Restrictive measures, shattered dreams

“My experience working with children has inspired me to study medicine. I have seen so many children with medical challenges, and I think I can do better practicing medicine and continuing to help children. I want to add more value to children’s lives and my community.

“However, that dream is impeded by the ban on girls from accessing university education and their ability to practice as professionals. I am one of the millions of young Afghan girls whose dreams have been destroyed by the restrictive measures imposed on women by the Taliban authorities.

“Young Afghan girls have aspirations. They want to explore and express their potential. They want to play their part in their own personal and professional development, and that of their families as well as their wider communities. Confining women and girls to home is worsening their situation and is a contributing factor to the deteriorating humanitarian crisis.”

*Name has been changed.