Lost in paradise: The struggle of migrants in Honduras

“I couldn’t tell you where this place is on the map even if I tried,” said a frustrated migrant.

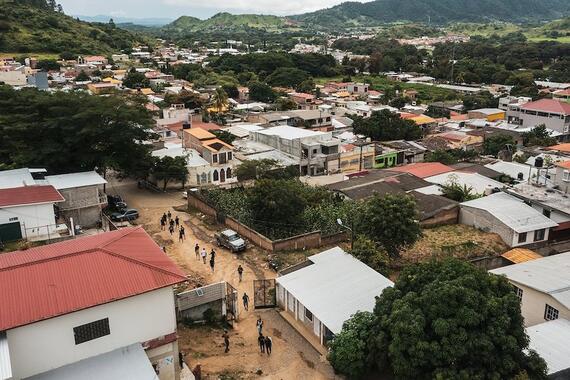

This place is El Paraíso – or “Paradise” in English – a once-tranquil Honduran department on the south-eastern border with Nicaragua that has seen the arrival of an unprecedented number of migrants from all over Latin America and the Caribbean, and the world, en route to North America.

Between 2010 and 2021, just under 2,000 migrants with an irregular status crossed into the Danlí and Trojes municipalities, according to the National Migration Institute (INM). But in 2022, that number ballooned to 141,290 – more than 70 times as many migrants as in the previous 11 years combined.

More than 229,100 migrants have already crossed into El Paraíso in the first half of this year, many of whom need assistance. With this flow showing no signs of slowing down, Honduras’ Congress is exempting migrants from paying a US$200 fine for entering the country with an irregular status, partly thanks to the tireless advocacy of the Honduras National Humanitarian Network. However, humanitarian partners are feeling the strain; their resources are already stretched with their ongoing efforts to support 3.2 million people in need across Honduras.

Many of the thousands of migrants arriving in El Paraíso have serious health and protection needs. OCHA/Vincent Tremeau

Many who arrive in Trojes, a small town of 54,000 people on the Nicaraguan border, made their way from Panama after crossing the treacherous Darién Gap, where authorities are also logging record-breaking numbers of entries. The dangerous route between Colombia and Panama, which links South and North America, has long been used by migrants trekking north to reach the United States.

“We saw bones, remains and bodies, like, 15 times a day,” said one migrant when asked about the Darién Gap.

Many migrants often cross into El Paraíso through “blind spots” (informal entry points away from official crossings), where the only things dividing Honduras and Nicaragua can sometimes be a barbed-wire fence and trees.

Buses in Nicaragua drop off 30 to 40 migrants at a time near these blind spots. Migrants then walk into Honduras before moving towards the centre of Trojes, just up the road.

In Trojes, the streets around the INM facility are teeming with tired migrants looking for answers. INM officials struggle to keep pace, resulting in longer wait times in queues. Eager to keep moving, some people settle next to INM offices so as not to lose their place in the queue, while others opt for nearby shelters that are often over capacity.

Migrants in Trojes either crowd around migration authority offices seeking answers or wait in long queues.

No one chooses to arrive in Trojes. In fact, many don’t even know where El Paraíso is.

“Smugglers are leaving us in a place we don’t know, where there are fewer official services, so their network can keep draining us of our money,” said a migrant.

Left in such vulnerable conditions, these people must fend for themselves in the streets amid harsh conditions that can vary between sweltering heat or pouring rain.

Migrants in Trojes are sometimes left to wait in harsh environmental conditions.

“The whole world needs to see this; this isn’t a game!” shouted one migrant.

With response capacities overstretched, authorities often bus migrants 70 km west to Danlí, a municipality of 222,000 people.

Migration authorities in Trojes bus people to Danlí, another municipality with larger offices and shelters. OCHA/Vincent Tremeau

But for every advantage Danlí offers, there is a challenge. Larger INM offices means longer queues. More space means more makeshift camps. Larger shelters means more people who need response. Larger groups means more disorder.

“There isn’t much order to any of this. We’re more or less self-organizing,” says Daniel, 26, a Venezuelan who reached Danlí with his friends.

Some migrants take part in a self-organized numbering system to try and make orderly queues to enter the migration office in Danlí. OCHA/Marc Belanger

Daniel has “293” scrawled on his forearm as part of a self-organizing system, indicating their order of arrival that day to note their place in the queue. However, this doesn’t work if others don’t do the same. It is unlikely Daniel will be the 293rd person to enter INM since his arrival.

Moisés, one of Daniel’s friends, chimes in: “The ones who don’t understand Spanish, they just get in the queue anyways. There are no bilingual officials to help, either. It’s a mess.”

This mess is often on full display through long and disorderly queues of two blocks or more, which can lead to tensions spiraling out of control.

Migrants have to stand in long, disorderly queues and often stay in makeshift accommodations outside migration offices for answers and support. OCHA/Vincent Tremeau

When the INM office opens late, the frustration can be heard in several languages, including Somali, Spanish, Haitian Kreyòl and French from West African countries.

People from all over the world are receiving assistance in El Paraíso. OCHA/Vincent Tremeau

The majority of people crossing into El Paraíso are from countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, but hundreds come from places as far away as Afghanistan, Angola, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Eritrea, India and Uzbekistan, among others. Most arrive in South American countries that have fewer visa requirements and then make their way north through Darién.

INM offices allow only five people in at a time. After processing, people have five days of safe passage to leave Honduras. Parents with small children are generally admitted first, indicating a priority system based on vulnerability.

The Danlí INM office generally admits parents with small children first, leaving the rest to wait under El Paraíso’s unforgiving sun. OCHA/Marc Belanger

Some choose to return to INM after resting at the Jesús Está Vivo (“Jesus Is Alive”) church a few blocks away. Partners helped turn the church into a shelter before its December 2022 closure. It was one of the few places in Danlí where migrants received assistance before official shelters opened in 2023.

The church housed up to 250 people, despite Danlí receiving between 700 and 800 people a day. Most left the church the following morning, leading to high turnover.

The Jesús Está Vivo church in Danlí saw a high turnover of migrants using it as a makeshift shelter before returning to the INM office the next day. OCHA/Vincent Tremeau

This limit also meant that Action Against Hunger, with support from the UN Children’s Fund and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, had a predictable target for delivering daily food rations and child nutrition screening services.

Partners such as Action Against Hunger provided daily food deliveries to migrants at Jesús Está Vivo church. OCHA/Vincent Tremeau

While at the church, 30-year-old Geraldine, from Venezuela, shares an all-too-familiar story about her family’s journey through the Darién Gap to reach the United States.

Geraldine says that they were often at the mercy of smugglers who would abandon them. They would then have to hire the services of more smugglers, forcing them to deplete their limited resources.

“It’s been complicated, we don’t have any more money, but we’ve made it this far,” she said.

A businesswoman by trade, Geraldine says she seeks an honest job in the United States to provide for her children.

“A better future and education for my children. That’s all I want.”

Footnotes Text: Marc Belanger - Map: OCHA - Photos: Vincent Tremeau and Marc Belanger - Edited by: Nina Doyle