Syria: From orphans to earthquake survivors

By Madevi Sun-Suon with support from Anastasya Kahala Atassi at OCHA Türkiye

My wish for the new year is for the war to stop so we can go back home where there is food, warmth and laughter,” said 12-year-old Ahmad.

Ahmad and his brothers, Hammoud and Nouri, live among 30,000 other people in one of north-west Syria’s biggest camp clusters. Their home is a tent made from flimsy fabric.

But in the past year, life for the three brothers was even more difficult; they were orphaned in January 2023 and endured devastating earthquakes just one month later. When all seemed lost, hope came in a most unexpected way: a reunion with a long-lost cousin.

Finding family after the earthquakes

Ahmad, his two brothers and their mother previously lived in a village in Aleppo. But when increasing hostilities made it unbearable to stay, they fled to Idleb in 2019, taking refuge in an informal self-settled camp in Dana.

Then, in January 2023, their mother unexpectedly fled the camp. She was the household’s only adult, as their father was killed in an air strike some years ago.

Ahmad and his two brothers suddenly found themselves alone. Hammoud was the oldest, at only 16. Their tent was far away from other camp residents, with no electricity or heating, which only heightened their isolation. Each night was shrouded in oppressive darkness for the three boys.

From there, things only got worse.

When the earthquakes struck Türkiye and Syria on 6 February at 4:17 a.m., the three brothers were woken by continuous jolts swinging their tent back and forth. Ahmad was used to rain and snow, which are common in Syrian winters, but he’d never experienced such tremors in his 12 years.

“We didn’t know what to do except hold each other and cry. All that we could see was darkness,” he recalled.

It wasn’t until a month later that the non-governmental organization (NGO) Al-Sham Humanitarian Foundation (AHF) received alarming information from a community committee: three brothers were living on their own in a camp, surviving on handouts.

Aid workers finally found Ahmad, Hammoud and Nouri in the Al-Dana camp in March – two months after their mother’s disappearance.

“It took us some time to find them,” explained Mus'ef Alsalamah, AHF Field Team Leader, who was following up on family separation cases.

“We had to prioritize areas most affected by the earthquakes, focusing on neighbourhoods where homes had collapsed.”

When Mus’ef and his team asked the brothers if they knew of any other living relatives, they could provide only the name of their older cousin, Mohammad, and a vague recollection of the name of a village he fled to in 2019: Tal Al-Karama.For three months, Mus'ef and his field team from AHF scoured the cluster of camps in Tal Al-Karama to find Mohammad, moving from tent to tent like detectives on a trail. Data from the CCCM Cluster (organizations specializing in camp coordination and camp management) indicates that at least 1,000 people live in 14 of Al-Karama’s 17 camps. But the search was further complicated by the geographical terrain, which, according to Mus'ef, made it “almost impossible” to distinguish boundaries between registered camps and informal sites where families settled on their own.

“It was an exhausting process,” recalled Mus’ef. “We spoke with each camp manager, starting with Camp 1, but not everyone was cooperative or had the official names of residents.”

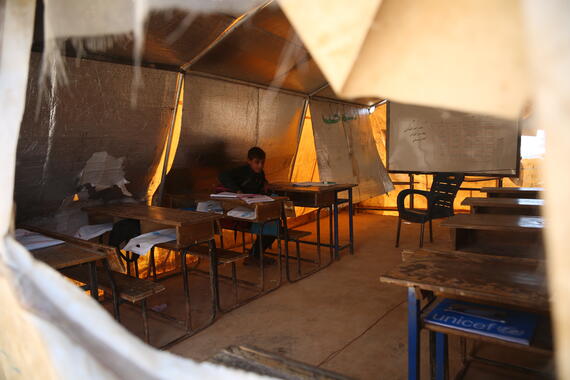

Meanwhile, back in the Al-Dana camp, another AHF team held weekly counselling sessions with Ahmad, Hammoud and Nouri following an assessment of their needs. The boys, who were still rattled by the ongoing aftershocks, also received food assistance. To help restore confidence and rebuild trust in their environment, they were integrated into activities with other earthquake-affected children.

Three months later, in June, Mus’ef and his team finally found Mohammad, in Camp 17. They brought Ahmad, Hammoud and Nouri to the camp, and the cousins were finally reunited.

Mohammad broke down in tears when he saw his three cousins for the first time in three years.

“How could they be left alone like this?” he said. “And what’s more, how did I not know about it?”

According to the Protection Cluster (organizations specializing in protection), the number of child-headed households surged after the earthquakes due to so many children being separated from their caregivers.

AHF’s family reunion initiative is one of nearly 160 projects funded in 2023 by the Syria Cross-Border Humanitarian Fund (SCHF), managed by OCHA Türkiye to address needs in north-west Syria ranging from food and shelter to child protection. Over the past year, SCHF allocated US$140 million to help 2.8 million Syrians. More than half of the funds went directly to Syrian NGOs like AHF, who are on the front line of the response.

As early as the first day after the quakes, family-tracing surveys were disseminated to affected communities, starting with residential areas where the death toll and building collapses were high. For example, Jandairis, in northern Aleppo, was among the prioritized towns with more than 1,000 lives lost, constituting one fifth of north-west Syria’s death toll. For these reasons, displacement camps were considered secondary targets for family tracing.

Surviving 12 years of conflict

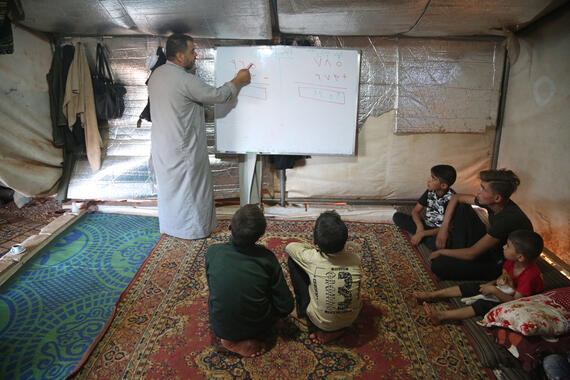

A teacher in the camp and a father of five, Mohammad is dedicated to helping children reach their full potential. But in the context of Syria, where war has raged for nearly 13 years, even simple aspirations are an uphill battle.

In the winter, challenges are multiplied tenfold as temperatures plummet below freezing. For the 800,000 people residing in tents in north-west Syria, each morning begins with a personal assessment of the weather: Will it rain? Will it flood? Or, even worse, a combination of both?

The family received a heater among the aid distributed ahead of the winter season. But faced with fuel scarcity, they resorted to burning whatever items they had, including an old pair of jeans and olive waste, known among Syrians as birin.

Mohammad said: “We are doing all we can to survive these cold months. Children have been collecting cartons in the morning to burn and stay warm.”

Winter hardships are only a fraction of people’s everyday reality in Syria

The country remains one of the world’s largest internal displacement crises; at least 3.4 million people are internally displaced in north-west Syria alone – an increase of more than 500,000 people from 2023. The majority live in camps or self-settled sites, often in health-threatening overcrowded conditions with limited access to water, electricity and other basic services.

Over the past year, the Tal Al-Karama camp, now home to Mohammad, Ahmad and his brothers, has been supported by the UN and its partners through cross-border assistance, including food distribution, sanitation support and protection services.

But communities still grapple with unpredictable pockets of hostilities, and they live in fear of when the next incident will occur.

Since October, shelling and air strikes have affected more than 3,500 locations in Idleb and western Aleppo, making it the most significant escalation of hostilities in north-west Syria in four years. More than 100 civilians were killed in three months, nearly 40 per cent of whom were children, and more than 440 others were injured.

When shelling struck areas close to the Tal Al-Karama camp, Ahmad recalled the rumbling sounds being like thunder. “It was impossible to sleep after that. I kept waking up throughout the night until morning,” he said.

Mohammad added: “Even if these incidents are relatively far from our camp, we never know if our tents could catch fire from an explosion or if our children are safe.”

2024: A year of cautious hope?

“They were not only isolated, they were invisible,” stressed Mohammad, referring to his cousins’ lack of legal identity when they first arrived at their new home.

At least 89 per cent of the 2 million children in north-west Syria require child protection assistance, including psychosocial support and specialized services. Many also lack registration cards, birth certificates and other documentation required to access humanitarian assistance.

“It is not possible to go to school or receive aid if you don’t have a proper form of identification,” added Mohammad, who has since registered his young cousins for their ID cards.

Today, Ahmad goes to school and dreams of being a teacher, just like his cousin, Mohammad.

His favourite subject is Arabic. In his free time, and during last summer, he enjoyed playing football and other games with children in the camp. He also helps the family with household chores, such as securing their tents with rocks and heavy objects to secure them on windy days.

Ahmad shared his reflections:

“It’s been a long time since the earthquakes, back when we didn’t have any friends. Now, I have my brothers, my cousins and my classmates. I don’t feel scared anymore.”

Amid these glimmers of hope, the outlook for 2024 remains largely bleak for communities and humanitarian workers.

Over the past year, the World Food Programme (WFP) provided food baskets to the camp hosting the cousins. However, this year, due to funding shortfalls, WFP was forced to suspend its food assistance programme in Syria, which provided food aid to 1.3 million people in the north-west alone. The start of this year revealed other dire consequences of underfunding, including the suspension of support for water stations, education activities and health services.

“People who were coping with two meals a day will be forced to eat only once a day now. We are living at the lowest [level] to survive,” Mohammad said.

Funding for the 2023 Humanitarian Response Plan for Syria, which requested $5.1 billion, was only 38 per cent funded by the end of 2023, making it the most underfunded plan for Syria since the war began.

March will mark 13 years of conflict in Syria. But as the spotlight wanes from protracted crises like Syria, Mohammad shared his message to the international community:

“The world needs to view Syria with humanity. The conflict is still ongoing, and our suffering must be seen through the same lens as other crises.”